|

For those of you who don’t like personal stuff in blogs,1 you can stop reading right now and come back next year. If you can stand the personal view, then read on.

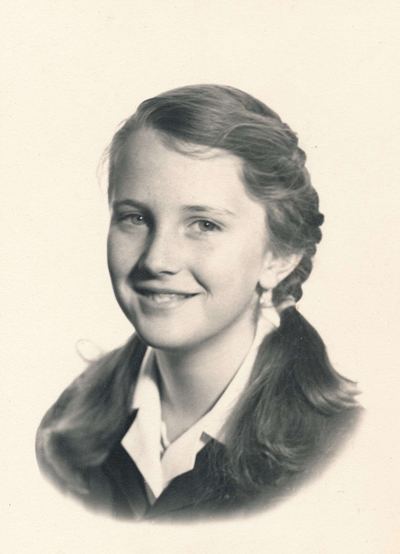

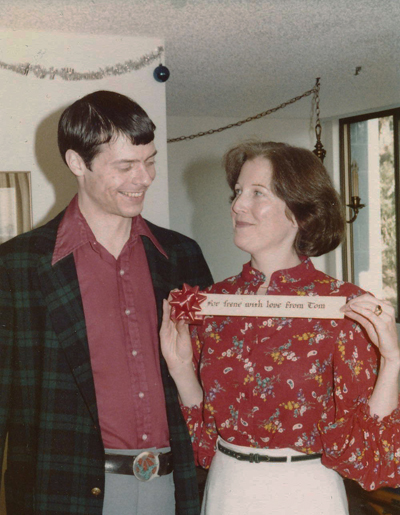

It’s been more than three months since my wife Irene died in early September. By now, I have gone through all her desk drawers, sorted years of old financial records from her photographs and memorabilia, and hauled the resulting boxes of wastepaper to the shredding service. I have also gone through her armoire and her various closets, separating slacks and tops from sweaters and jackets, bundling underwear and socks, and taking piles of clothing to Goodwill Industries. And, as of this writing, my co-trustee and I are in the final stages of closing her bank and credit card accounts, making the bequests in her will, and transferring her retirement accounts according to her instructions.

All of this is part of putting away a life, as much as taking her ashes to the gravesite and holding a remembrance in her honor among family members and friends.

What struck me is how long all this took.2 We all know that wills take a while to process, even if the deceased had a living trust, designated clear beneficiaries for each account, and the estate does not go to probate. Still, the companies that offer investment vehicles such as individual retirement accounts and annuities can need weeks to complete the paperwork that transfers the ownership and moves the assets into a trust account. But all that’s just on the legal and financial side.

Part of the delay in wrapping up the rest of her life was my own sense of emotional inertia. I managed to go through the drawers of old bank statements and receipts in the first couple of weeks after Irene died. Partly, this was because it was easier to deal with these paper records, which have an impersonal and antiseptic flavor to them. Partly, because I needed to find documents like the deed to the condo, title to her car, and any surprises like unacknowledged debts and obligations, before the legal part could proceed. Irene managed our household finances as part of the arrangements governing our marriage. We always kept separate bank accounts and credit cards, because Irene didn’t really trust me with money.3 So going through her accounts was a voyage into terra relatively incognita and once jealously defended.

I found it harder to go through her closets and prepare her clothes for donation. Partly, this was a lack of urgency, because those clothes weren’t going anyplace soon and I didn’t need the extra closet space. Partly, it was the personal nature of the exercise. Somehow, sorting her entire wardrobe for disposal brought home, as neither sitting in the lawyer’s office nor closing her the bank account could, that Irene was really gone and wasn’t coming back. Not at all. Not ever.

As with the paperwork, Irene’s closets were also an unknown area in our lives.4 My wife—and all women, I think—like to keep their wardrobe space private. Even though we dressed and undressed in the same bedroom, she wanted to appear to the world—and that included me—as a completed presentation. Her decisions about the components that went into the look of the moment—this top with those slacks, this sweater or jacket—were supposed to remain a relative mystery. She never asked for my approval of any piece of apparel. And Irene did the laundry anyway; so she could keep her clothing arrangements entirely separate from mine.

It’s not like I did no chores around the house. She managed the laundry as a preferred activity to vacuuming and dusting, because she hated the noise, the smell, and the routine dirt of those two chores. I didn’t mind cleaning the house, but I didn’t care for the dampness, fumes, and critical timing of running loads through the washers and dryers down in the laundry room. So, for forty years, we traded off these tasks. And then, I could cook but not as well as Irene, and she was more adventurous with recipes—my meals being a bachelor’s basic fare of homemade chili, hamburgers and hotdogs, pizza from scratch, and other fast-food staples. Oh, and bread, because my mother insisted her boys know how to bake. After Irene retired, she took over most of the cooking and mostly had fun with it. And because she had the car and reserved rights to the condo’s one assigned parking space, while I rode a motorcycle as my basic transportation, she did most of the shopping, which became part of her keeping the household accounts. And finally, we traded off walking the dog four times a day, because when you live in a twelfth-floor apartment, you can’t just open the back door and let the animal run out into the yard. Of such long-standing agreements is a marriage made.

Now that she’s gone—in fact, from the first week after she died—I inherited all of these chores for myself. And it’s surprising how small a deal they really are. I reverted to my bachelor routines of forty years ago for assessing and doing the laundry and shopping for my groceries. As with the cleaning, I organized these tasks into basic routines, put them on a schedule, and started executing them efficiently.

They say that when you start drinking again after a long period of abstinence, you don’t start over again with fresh tolerances and work your way back up to heavy indulgence. Even after years, the body remembers exactly where you left off. Stay sober for decades,5 and within a week of taking that first drink again, you’ll be downing a bottle of wine or a couple of six-packs a night. So it is with the routines and skills you develop early in bachelor life. Irene had little quirks about performing her chores: how to fold the towels, which items to let air-dry, how to load the dishwasher—even after I had already put my dishes in—and what pans had to be scrubbed by hand. Within two weeks after her death, the linen closet and the dishwasher looked like my bachelor days. Not less neat, and certainly not less clean, but just different. And I’ve also started modestly rearranging the furniture according to my own ideas, rather than the placements we could agree upon—or fail to reconcile—together.

But forty years of living with one person leaves a mark—no, the years wear deep grooves in your psyche. I may be adapting now to the old patterns of taking care of myself. But sometimes I hear a rattle in the hallway. I know it’s the wind, but I think it’s Irene with her keys. The dog hears it, too, and her head comes up and her ears go erect. I hear someone say, “Tom …” in a crowd, and it’s in Irene’s tone of voice. I know she won’t be coming back—I’ve done the necessary sorting and packing away—but she is still there at the edge of my mind.

The condo which was enough for two people now feels too big and empty.6 I feel like David Bowman from 2001: A Space Odyssey, alone at the end of his voyage in an absurd French-empire hotel room, listening for someone to come, for something to happen. But I don’t exactly listen, because I know I’m alone. Yes, I have friends—most of them associations that Irene and I made together—and family members in the area. But the days are long. And thank heavens for the dog as a companion to give the apartment some life. Thank Irene, actually, because this particular dog was her choice—it was her turn to pick—at the animal rescue shelter.

But now I’m caught at the end of my life, too old to start over. I’m wondering what, if anything, comes next.

1. Of course, my blogs are all personal, but some are on a higher intellectual and emotional plane than this.

2. In the recent movie Arrival, the heroine asks about one of the aliens who has gone missing after a bomb attack. Her interlocutor replies, “Abbott is death process.” I now understand that phrase, “death process,” all too well.

3. In every relationship, one person is always the Grasshopper from Aesop’s fable, while the other is the Ant. Guess who was the Grasshopper? In the same way, in every relationship, one partner is always Oscar from the Odd Couple, while the other is Felix. Guess who was Oscar?

4. One thing I learned from handling every piece of Irene’s clothing is how lightweight and insubstantial women’s clothes really are. Men’s slacks are made of heavier material and then thickly sewn with substantial waistbands, belt loops, gussets, and lots of pockets. Men’s shirts usually have reinforced collars, shoulder yokes, button plackets, and one or two chest pockets. Women’s slacks and blouses are thin material with hidden seams and virtually no pockets. Even items that would seem to be common to both, like polo shirts, are made of a different weight of yarn or a lighter weave. I guess this is because women’s clothing is supposed to drape and cling, while men’s clothing is meant to be essentially shapeless.

5. I now have thirty-two years of sobriety, and forty-four years without tobacco, both after going cold turkey for the sake of my health. Not that I’m thinking about starting up either vice again.

6. Friends keep asking if I plan to stay there or move. This was the home Irene and I moved into when we first got married and we never left. Partly, that was because we didn’t want to be house-rich and cash poor at Bay Area real-estate prices. Partly, it was because we never could agree on any other house we saw or any move we might make in any direction. But the condo will always be Irene’s-and-mine and not mine-alone. I think this is what my friends sense.