|

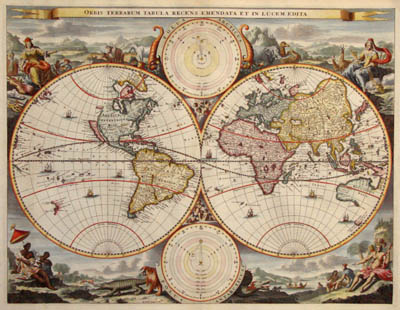

Cartography, the art of making maps to record details of a patch of ground in human-usable form, is an artificial and abstract art. It’s artificial in that, when you come right down to the process, the map itself bears no physical relation to the surface it records. It captures none of the details that a human being standing on the ground would see, nothing that looks like the symbols on the map, not the trees, not the mountains, not the buildings. And the product is abstract in that, when a person tries to put the product to use, he or she must supply an intermediary step, that of knowing what the symbols represent and how they were used to depict the ground in two dimensions.

We might think that map reading is intuitive, but actually it’s an acquired skill. Most of us—or at least I did—picked it up at home, first from watching our parents use maps, and then by asking questions and following along ourselves. If the skill is taught in school anymore, it probably comes in the second or third grade, when the curriculum starts differentiating “social studies” from reading, writing, and arithmetic. By the time a child is studying anything so formal as “history,” he or she is expected to be able to look at a map and know the conventions, such as that the top is “north”—at least among those of us who are European descendants—and that some of the squiggly things are roads while others are rivers. If you went to the outback of Australia or the rain forest of Brazil and handed a map to an aborigine who has had no contact, or almost none, with civilization—if such people still exist in this day of satellite dishes and continuous, invasive explorations—that person would not know what to do with it. For him, it’s just a piece of paper with squiggles and colorful blotches. And when told that it describes the land surrounding him on all sides, his response would likely be, “Um … no.”

Anyone who has spent any time with antique maps knows that the conventions of cartography have changed over the centuries. Modern surveying techniques, exact measurements, and now satellite photographs have all made the details a lot sharper and more reliable. We no longer show mountains as little pictures of lumpy hills, representing the peaks only from the perspective of someone hanging fifty thousand feet in the air along the southern edge of the map—while the rest of the information pretends to be a vertical projection, invested with meaning only when viewed straight down from the document’s midpoint. We no longer draw little trees for forests or tufts of weed for swamps. For simplicity, modern maps like those used in schoolrooms show elevations as colored backgrounds, with the lowest areas usually in bright green, shading through yellows and light browns for the plains, to dark browns and reds for the highest peaks.1

A more detailed map—such as one you would use in hiking over rough ground—uses contour lines that try to represent a three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface. And again, it takes skill to read this kind of map. You have to supply that intermediary knowledge step to understand that each line represents an equal increment in elevation—and then to realize that where those lines are far apart the slope is gradual and the walking easy, and where they are close together the ground is actually a cliff face and you’d better bring ropes and pitons.

Maps are also drawn for specific purposes. A roadmap, such as you once could buy at a gas station—back when they serviced all of a driver’s needs, not just gasoline, packaged foods, and big drinks—and now you must get from AAA®, are designed to show a dozen different grades of road, from dirt track to superhighway. But such a map is going to be vague on the subject of mountains, forests, lakes, and rivers—other than to show where the bridges and ferries are to be found. Conversely, a riverine or marine chart is extremely accurate about soundings, snags, buoys, and bearings but leaves the dry ground completely blank except for details like wharves and docks right at the water’s edge.

These days, with the ubiquitous smartphone putting gobs of online data in your hand, mapmaking as a representation intended for paper viewing is dying out. Maps are now compilations of all these details—filtered according to the application—on a screen that orients itself and picks the scale according to command and scrolls along as the user moves from one place to another. And now Google Earth does away with the abstract map entirely, showing you an actual photograph of the ground, taken by a satellite in orbit, with the ability to fly you down to “street level” and view photographs of the surface taken by a roving camera sometime within the last year or two. This is no longer a map requiring that intermediary knowledge step but a stop-action video of the ground itself that any aboriginal Australian or native Brazilian would be able to recognize—if the Google camera cars ever went to the Outback or traveled up the Amazon.

In the same way,2 language is an artificial and abstract way of representing the complex reality that we humans find all around us. It’s artificial in that no word or phrase is an exact copy of the thing or place being described. It’s abstract in that the hearer or reader of a statement made with language must supply an intermediary knowledge step involving the meanings and often the connotations of the words themselves, the mechanics of grammar and syntax, and an experienced ear to distinguish the sloppy, elided speech of everyday communication from the parsed and precise language as taught in school. Such knowledge must exist before he or she can appreciate the content and intention of the communication or description. If you don’t think this intermediate step is necessary, try walking as a non-Chinese-speaking foreigner into a bakery in Beijing and ordering a donut.

Just as maps have evolved from depicting mountains with lumpy little hills and forests with picturesque tree shapes, so human language has evolved—and it in all its forms is constantly evolving, adapting, and growing more precise and specific. If you read a history of language like John MacWhorter’s The Power of Babel, you can see that language as spoken is not the product of dialect pressures and slang usage working on neatly separated language families like “English” and “Spanish.” Instead, every person, as a member of a local group or affinity, speaks and writes with a set of evolving symbols and meanings. Spanish, as MacWhorter shows, is nothing but a dialect of Latin that has softened, morphed, and changed over the centuries on the Iberian Peninsula after the Roman Empire withdrew. Similarly, French is a dialect of the same Latin which evolved in northern France, while Italian is Latin that has developed in place on the Italian Peninsula. And English is just a cracked and crazed horror—the result of a millennia-long culture clash between the native Celts and the conquering Romans that was then warped and shaped by successive invasions from Northern Germany, Denmark, and French Normandy. And all of these languages went through another convulsion in the past six centuries or so, when mathematical thinking based on Arabic terms and scientific thinking based on Greek terms arrived with the Renaissance and the Enlightenment.

Just as maps are used for particular purposes—hiking, driving, or marine navigation—so languages have developed specific words and constructions for defined purposes. Two doctors discussing a patient will use precise medical terms and adopt a peculiar perspective of diagnosis (what is happening now) and prognosis (what will happen in a future with and without treatment) that the patient might only dimly understand. In the same way, two physicists discussing quantum mechanics, or two programmers describing a piece of software, will quickly subside into specialized terms—quarks, leptons, bosons, vectors … or RAM, ROM, gates, loops—that the lay person can only follow with much difficulty and then with a high potential for misunderstanding. Again, the average person doesn’t have that intermediary knowledge step, just as a speaker of English-only is lost in the Chinese bakery.

In dealing with maps, soldiers and other practical users must constantly remind themselves that “the map is not the territory.” You might think that you can plan an attack or defense in great detail just by working from a map. But maps are still artificial and abstract constructs. The slope you believe might be gradual enough for a team of soldiers to charge up carrying full packs and equipment turns out to be much steeper. The team is delayed—or cut to pieces in a crossfire. So a good officer tries to see the ground, perhaps by aerial observation, probably by walking over it in person, before committing to an action. In the same way, a ship captain knows that the chart may not include all the nuances of current and wave action common to an estuary or harbor and so employs a pilot who knows those waters. And a hiker discusses the trail with others who have walked it before committing his or her life to the wilderness.

In dealing with language, writers and other practical users must constantly remind themselves that the terms and constructions they use may not be understood by everyone who encounters the text. A good writer—whether of fiction like a novel or nonfiction like a technical manual—is constantly advised to think of the intended reader, imagine that reader’s familiarity with the intended words and concepts, and work through the differences. A technical manual to be used in a closed industrial setting will use different norms from the manual intended for home use in assembling a piece of furniture or operating a stereo set. A novel written for a science fiction audience will use different concepts, structures, and devices than one written for the romance or mystery reader.

But unlike a map, where the thing being represented is open ground and available to any set of eyes, the reality that language tries to capture is usually private and personal—at least for those of us who write fiction. What is the shape of love? Of frustration? Or rage? We cannot uniformly represent these abstract human realities with contour lines or graded roads. Instead, we must talk around them. We must present stories—circumstances, actions, results—that will elicit in the reader’s mind and memory the feelings we are trying to portray. I cannot accurately tell you the shape of love, but I can tell you a story about meeting and engaging with a particular person, living in their orbit and in their arms until their presence becomes second nature, and then losing that person to misfortune or misunderstanding, so that you can feel the delight and the pain in your own chest.

In this way, language is not just like a map, it is better than any map. Where a map is a two-dimensional representation of a three-dimensional surface, the power of language encompasses past, present, and future, involves both actions and reactions, and includes the dimension of feelings about those actions and circumstances, regret for things that never happened, hope for things that might be different … that is, a representation of the a vast, multidimensional universe that is the human mind.

That is what we writers are about: we are cartographers of the human soul.

1. The color range doesn’t go through blue, though, because that color is reserved for the water of rivers, lakes, and oceans. And here, the convention is that the darker shades of blue are the deeper bodies of water.

2. This is not an original thought, but it’s one that has been rattling around in my head.