|

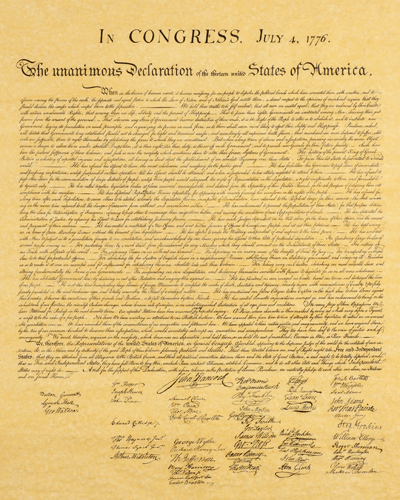

You know where in the Declaration of Independence, in the second paragraph, it says, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal”—I have always stopped right there.

To me, this is not a self-evident truth but fatuous nonsense. No two persons are or ever were equal. One or the other is always going to be bigger, stronger, faster, smarter, shrewder, more handsome, more sexual, more adept with women, better able to handle his money or his liquor, better at cards, better at life. No two things in this universe, not two stars or planets or galaxies,1 were ever “created equal.” So, for a long time, this statement—at the core of the Declaration—puzzled me.

But the idea of equality encompassing all these characteristics is actually a late 20th- and early 21st-century notion. To understand what Jefferson was writing about, you have to see this statement in terms of 18th-century suppositions2 and pay close attention to the clauses that follow.

The 18th century was a time when people were presumed to be divided at birth between nobles and commoners, lairds and crofters, lords and serfs, “the better sort of people” and “the rest of them.” This was a given: that a man (or woman) was born into a certain station in life, and that for a person to rise out of it—or fall from it—was a remarkable thing. “Rising above your station” was also contrary to God’s preordained intentions, because it was God who put you there in the first place; it was part of His plan for you. Changing one’s position in life violated the “Great Chain of Being”3 and was unheard of in the Europe of the Middle Ages and even into the Renaissance. People and their classes were fixed for eternity. But by the 18th century, in England at least, a prominent person of rather humble birth who had done good service to the crown or the nation as a military officer or politician might be granted a baronetcy, which ranked him as a minor lord equivalent to an old-fashioned knighthood with the privilege of hereditary transference. Sort of a back door into the club.

But in the American colonies, where people with actual noble rank were only visitors and not cast upon the distant shore to make their way or die, elevated station was not gained through inheritance—or not at first, and not officially—but rather as the product of holding large amounts of land as a scion of the early settlers or making or inheriting vast amounts of money in trade. And such holdings, along with their unofficial rank or status, could just as easily be lost through stupidity, ill fortune, or a bad turn at cards. By 1776, the notion that some people are born better than others, rightfully holding a higher station in life, favored by God, granted rights and privileges to which the common run of humanity was not entitled—well, that Old World view was pretty much blown. Or that was the mindset of the radicals of the time: Jefferson, Washington, Adams, and everyone else looking to start a new country on this continent.

And so we come to the clauses that follow: “that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” And that’s the nut of it. A free man on American soil was not a peasant to be bound to the land or ridden down on the road by a lord on his high horse. He was free to work where he wanted at the thing that made him happiest.4And it was hard to hold a man at a job in town or on the landlord’s farm when the whole colony occupied only the easternmost fringe of coastline—penetrating only one or two hundred miles inland—on a continent that spanned three thousand miles. Anyone dissatisfied with his lot could easily pick up an axe and a hoe, walk off into the woods, come to the first empty clearing, and start farming for himself.

So the Americans of the mid-18th century, the time of the Declaration, did not see themselves as anything less than King George, their lordships of Old England, or members of the Parliament that made rules for their American colonies. Americans were not of lesser station or deserving of less consideration or fewer rights because of their humble or obscure heritage. But at the same time, the concepts of life, liberty, and happiness embedded in the Declaration were understood to ensure only a person’s equal treatment under the law, which granted him or her equal rights and privileges. But the Declaration never meant to guarantee equal expectations and outcomes in life, because each person has to make those for him- or herself.

The distinctions between noble and commoner—or indeed between white European and black African—that weighed so heavily on the minds of 18th-century thinkers have now been worn away by two and a half centuries of actual judicial equality. For most Americans, our shared humanity is a simple matter of personal enlightenment in a society that already values equality. We have made a society where all men are truly equal before the law—or at least that is our stated intention, since the Civil Rights Act of 1964. And so the class and judicial distinctions that impelled the language of the Declaration no longer exist for us. This leaves the present-day reader free to imagine other, perhaps deeper meanings for the word “equal” in that context.

The old class system in England and in Europe generally—between the peasant and the lord—were systems to confer and maintain advantage and power. The families that attained leadership positions in the neighborhood or as adherents to the king, or those with large landholdings—usually the same thing, as land was generally gifted by the king as a remnant of feudal times—maintained these rights by passing them down to their sons and occasionally through their daughters. Noble titles usually accrued to such positions of power, and eventually the inherited title came to mean something even after the political power or the land and money were gone.

In America, although a person might be born into low station, that guarantee of liberty and the pursuit of happiness allowed the individual to pursue and maintain large landholdings—remember those three thousand miles of open land stretching to the Pacific Ocean—or earn vast fortunes through enterprise and industry. And the 19th and 20th centuries were a time of huge technical advances in mechanics and energy, which enabled many entrepreneurs to build great wealth, just as the late 20th and early 21st century now provide opportunities in cybernetics. By passing the wealth down through sons and daughters, wealthy dynasties not much different from European nobility have been built.5

But now, with a new reading of that “created equal”—focusing on the desirability of equal expectations and outcomes—the American spirit seems to want no inequality. There should be no systems of power, no wealth to be made for oneself and one’s family by hard work, prudent saving, and shrewd investment. The government, it is presumed, will see to it that everyone prospers equally, shares equally in the goods and services created by society—not by individuals or corporations or inspired inventors or from the fruits of personal labor, but by the faceless forces of society as a whole. That way, no one gets more than anyone else, and we will all be equal in fact as well as under the law.

Of course, that’s poppycock. Marx may have imagined that, after a brief struggle under the dictatorship of the proletariat, the state would eventually wither away, and everyone would settle into joyously producing according to his abilities and contentedly consuming according to his needs—forever. But Marx was a madman. In reality, in a nation with a large and diverse population and variously located farms and factories, and long-distance logistics, someone has to operate the distribution system, decide whose needs will be met, in what order, and when. That, my dears, is a position of power. And people with power will tend to profit by it and want to pass it along to their sons and daughters. It is in our human nature. That impulse created the new nobility of the Nomenklatura in the old Soviet Union and the ranks and privileges of Party members in every other socialist totalitarian state.

You can no more eliminate the concept of power from human society than you can eliminate sex or hunger, envy or greed. You can dampen the notion of ambition and make it generally distasteful to a large swath of the population. But someone will notice that the reins are flopping around on the horse’s back and take it upon himself to reach for them. That is in our nature, too.

So long as people are born with differences in the characteristics that count in life—some being smarter, some shrewder, some with more energy, or talents, or just with different dreams—equality in expectations and outcomes will remain a phantom, a figment, a madman’s goal, a utopia never to be found under heaven.

1. Except maybe for subatomic particles—like protons, electrons, and neutrons—but even there modern physics is having doubts about the construction of the Standard Model of quantum mechanics.

2. We also have to get over our modern feminist principles and the visceral reaction to that reference to “all men.” In the 18th century, the differences—or lack of them!—between the sexes and their roles in family and public life were not questioned. “All men” was not read as a distinction from or exclusion of women, but instead the phrase encompassed mankind—what we now are taught to call “humankind”—and the species H. sapiens generally.

3. The Great Chain of Being was a medieval Christian construct, intended to order the universe and everything in it from God Himself (the highest level) down through the ranks of angels, the classes of humans, then animals in the order of their natures and station in the food chain, next the plants, and finally the minerals (the lowest). Without a working knowledge of physics, chemistry, biology, and genetics, it was one way to bring structure to chaos and to keep the scholar’s mind busy.

4. Of course, indentured servants and chattel slaves were different, although early in the next century, if not in the 18th, people were beginning to question that assumption.

5. With the difference that these holdings can be lost through stupidity, changes in the marketplace, or a bad turn at cards. If you doubt this, ask yourself what has happened with the heirs to the Carnegie, Ford, or Kaiser fortunes. The pattern in this country is for an industrial empire to be built by an innovative entrepreneur, managed by the second generation or converted to a publicly traded corporation under a board and appointed managers, and if not converted, then generally lost in the third generation—unless the resources are put into a foundation, such as those of Carnegie and Ford, and managed for some public good.