|

All right, I’m an English major and became a writer from before I even got out of high school. Language and presentation are my thing—along with a penchant for clear reasoning. Being able to think logically and reason clearly is essential to any writer. Otherwise you get all balled up in your plot points, can’t make a convincing argument, and tend to wander off in the middle of an article or story. But I digress …

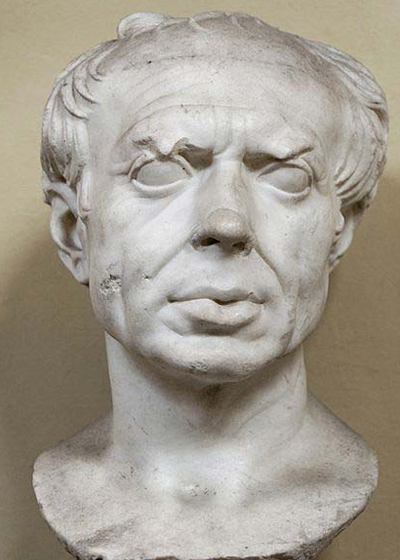

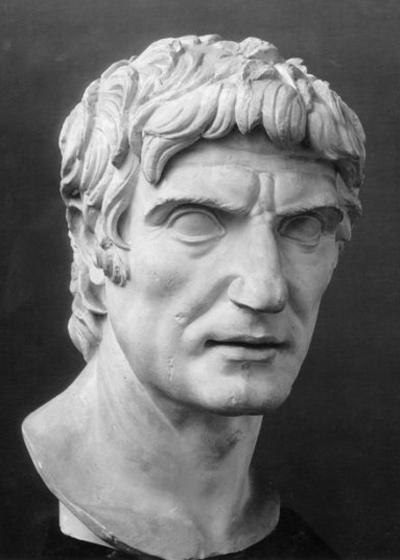

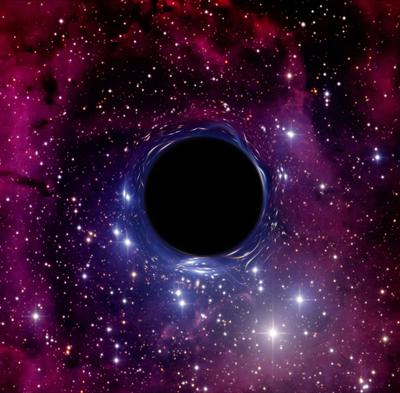

On the subject of cosmology, I’ve seen several recent articles including one in Scientific American and an episode of NOVA—a fairly popular press—suggesting that the galactic-core black holes, those with masses in multiples of a million of our suns, might have formed early on the universe’s time scale. The accepted origin of stellar-mass black holes is that they form from the collapse of large stars, ones so big that their cores after they burn out and explode don’t stop at the white dwarf or neutron star stage, but are so crushed by their inherent gravity that they disappear into a point and generate a timespace so curved that even light does not move fast enough to escape it.

In this theory, the galactic-core black holes must have started as regular collapsed stars, but they lived in a dense region of the galaxy with rich feeding opportunities. They tore apart all the stars around them, adding to their mass, until they became giants. And they went on absorbing any wandering nearby stars until they acquired the mass of a million suns. Although light cannot escape a black hole’s event horizon, the inrush of matter forms an accretion disk of colliding particles swirling faster and faster toward the center. And some of this jumble of moving matter escapes sideways as huge jets of energy at the black hole’s poles. These jets are some of the most energetic objects in the universe. Radio astronomers first identified emanations from these jets in the 1950s and called them “quasi-stellar objects,” or quasars.

The trouble is, by peering toward the edge of the known universe—which because of the time it takes light to travel over these huge distances is the same thing as looking backwards in time—we have discovered quasars in the earliest universe. Some of them at the center of the most distant galaxies are associated with black holes that must be less than a billion years old. In a universe that is supposed to have originated from a single point of matter that started expanding outward less than fourteen billion years ago, these earliest quasars—if they are indeed linked to galactic black holes—are an anomaly. The universe in its first few hundred million years, the age of these objects, could not have created the sort of massive stars that collapse into black holes in the first place. And it would not have created enough of these stars, in enough generations, for a stellar-sized black hole to have gobbled down thousands or millions more of its massive companions to become the objects we think we see today.

The conclusion of the articles is that some other accretion mechanism must account for these earliest quasars. The favorite theory seems to be that the central portion of these newly forming galaxies was so dense with dust and gas that black holes could form directly by gravity attraction. Before the mass of condensing material could kick off its fusion reaction and start burning as a star, the huge mass simply collapsed into a point of extremely dense matter concealed within an event horizon of closed spacetime.

Stars form—or at least that’s our current theory and observation—by condensing gas and dust into dense, whirling pools. When enough matter accumulates in one place, the inward pressure of gravity exceeds the outward pressure of the atoms beating against each other in a condensed gas. The compressed gas heats up and the lightest of these gases, the universally abundant hydrogen, start fusing into helium atoms. After enough time in the larger stars, the helium goes on to fuse as well, forming lithium, and later fusion reactions form carbon, oxygen, neon, and silicon. The process in even the largest stars stops at the formation of iron, which shuts down the fusion reaction and causes the star to collapse into a black hole.1

The notion that early galaxies had such dense star-forming regions that they would bypass the normal evolution we see and go straight to core-dominating black holes is a novel idea. I don’t necessarily find it rationally impossible. The idea of any material object collapsing to a point in a space that is too small to be measured but still containing tens, hundreds, or millions of solar masses is bizarre enough. That these collapse objects would create enclosed and unknowable systems—but that the universe itself was created by the outward explosion of a singularity that contained the mass of a hundred billion galaxies, each containing upwards of a hundred billion stars—that defies reason and logic. Infinite density in once case creates an undefinable and self-contained point, but an even greater density explodes with a force that causes the mass of the universe to spread outward, soon condense its raw energy into protons and other atomic particles, later to form stars and galaxies, and then go on to expand forever? Um, no …

And there’s a quirk to all this, too. The universe we can see with our instruments has a radius much larger than thirteen billion light-years. So while we can compute the age of the universe backwards to that point in time, it has actually been expanding away from us faster than the speed of light. Some astronomers account for this by the inflation theory—that in the first micro-instant after the presumed Big Bang, all the matter in the universe was actually moving faster than light, proceeding from an object the size of a proton or atom to a globe about the size of our solar system practically in no time at all. After that, the expansion slowed and the universe took on the shape we see today.

Of course, it’s no good asking where in the universe the Big Bang actually started. Everyone knows it started three inches behind my bellybutton. Or maybe behind yours. The point is, when you have an entire universe created from an origin with no dimensions, the starting point is actually everywhere. In an analogy I’ve used before, imagine four people are sitting at a card table at the center of the fifty-yard line on a football field when a bomb goes off under the table. The blast throws one person to either sideline, one back to the thirty-yard line at one end of the field, and the last person to the opposing thirty-yard line. If you ask each one where the bomb went off, they would point back to the fifty-yard line and say, “Over there.” But suppose they were sitting in a darkened room, and the force of the explosion threw them back an unknown distance in an unknown direction. Ask the same question, and their replies would all be, “Right here.” When there is no established field with no reference points, all origin points are the same.

We live in a universe that is supposedly thirteen-point-something billion years old, but which may be more than twenty-six billion light-years in diameter. Its earliest observable components have characteristics that we don’t really believe could yet have formed. The galaxies in this universe spin their stars with a velocity that does not match what we can understand about the gravity interactions of normal matter—causing our physicists to theorize about and search for evidence of “dark matter.” And those galaxies themselves are flying apart at an ever-increasing speed, far exceeding the impetus of the Big Bang itself—causing our physicists to theorize about and search for clues to “dark energy.” And these dark components are not just an add-on to the story of the universe we can see but, according to all the calculations we can make, they are the central facts of this universe. Compared to dark energy and dark matter, the stuff that makes up the world we know about is an irrelevance, a bit of foam on an ocean wave we cannot even detect.

But then, of course, we live in a universe bounded by c, the measured speed of light. And while that speed is constant and not to be exceeded in the vacuum of space, it is still a measure dependent upon both time and distance. However, Einstein’s own theory of general relativity says that time slows down and space curves inward under conditions of extreme gravity. This would seem to contradict his theory of special relativity, which states that the laws of physics are the same in all inertial frames of reference and that the speed of light is the same for all observers. Am I the only one who sees a conundrum here?

As I have written before,2 I believe there are three things we do not fundamentally understand in physics: gravity, space, and time. We can measure them. We can write equations about them. We can fit them into our conceptual mathematics. But we don’t—yet—have a working understanding of what they are. Time is not just the passage of seconds or the sequence of events. Space is not just an emptiness that does not happen to be occupied by bits of matter, which can then be resolved into tiny knots of energy. And gravity is not a force or a field, and it may not even be the resolute manipulation of the passage of seconds and the nothingness of space.

But what do I know? I’m just an English major. But I’m also an agnostic and a contrarian, which means I am suspicious of organized religions and schools of thought, whether they deal with the orthodoxy of an origin story based on seven days of willful creation or the explosion of an infinitely dense piece of matter. For me, neither story adds up or makes complete sense.

1. The heavier elements, including metals like nickel, copper, silver, gold, and uranium, form in the brief bursts of fusion during the catastrophic explosion and collapse of massive stars—or that’s the theory. This would account for their rarity both on Earth and elsewhere in the universe.

2. See Fun with Numbers (I) and (II) from September 19 and 26, 2010.