|

|

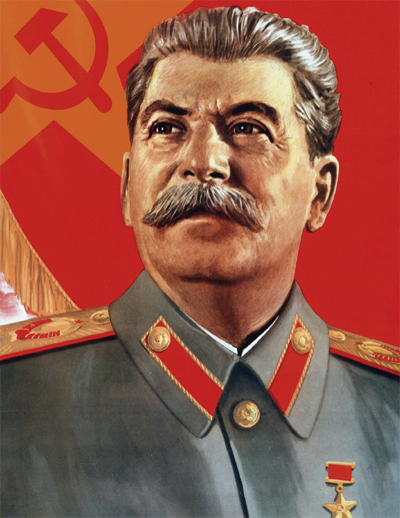

Joseph Stalin |

I am becoming more and more concerned about the direction of politics in this country.

It used to be—back when I was growing up, and for a decade or two afterward—that Democrats and Republicans could be civil to each other. They might differ on policy issues but they agreed about the principles and process of governing. Their disagreements were more about emphasis and degree than about goals and objectives. We debated a larger or smaller role for the public and private sectors, for amounts of taxation and regulation, for our stance in international relations, for the uses of military force versus diplomacy, and for other aspects of life in this country. But we could all agree that the United States was and would remain a country of individual liberties, rights, and responsibilities, functioning in open markets that supported investor capitalism, and with sovereign powers and responsibilities in the larger world, all under a government structure spelled out in the U.S. Constitution. These things were the bedrock of our society.

Yes, there were fringe groups. In the late 1960s, radicals on the New Left demonstrated not just against a war they didn’t like but actually in favor of our Cold War enemies in the Soviet Union and China, as well as for our “hot war” enemy in North Vietnam. They envisioned an end to capitalism and the introduction of a Communist-style command-and-control economy in this country. They wanted to overthrow the U.S. government in a violent revolution. The Students for a Democratic Society and their adherents marched for it, and the Beatles sang about it. But reasonable people in the mainstream parties ignored them—or called them “crazies”—and went about the business of governing.

Some of those New Left radicals grew up and matured but never abandoned their extremist principles. Saul Alinsky became a “community organizer” and wrote his signature work, Rules for Radicals. Bill Ayers, one of the founders of the Weather Underground, became an education theorist but remained in his heart a domestic terrorist. One of Alinsky’s admirers—she actually wrote her senior thesis at Wellesley College on him—was Hillary Rodham Clinton. A Democratic politician who was early-on linked to Ayers in Chicago was Barack Obama. But Obama’s and Clinton’s associations can be written off as errors in judgment due to their youth.

Now, and for the past dozen years or more, the internal direction of this country has shifted. The radical viewpoint has grown from a splinter at the extreme left of the Democratic Party to a driving force in much of that party’s current policies and rhetoric. In recent years, many Democrats have expressed sympathy with “Democratic Socialism,” which joins political democracy with government ownership of production and distribution. Many Democrats now favor open borders and the surrender of national sovereignty. The want a free-form and non-originalist interpretation of the U.S. Constitution, including revision of the First Amendment, abolishment of the Second Amendment, and elimination of the Electoral College. The largest unionized group in this country is now the public sector, which bargains for increased pay and protections from politicians who are not negotiating with their own money. That’s an idea that even so liberal a politician as Franklin Roosevelt thought disastrous and ought to be discouraged.

Since the presidential election of 2016, many Democrats have been in open revolt. Celebrities have called for bombing the White House. And seemingly rational people proclaim the current incumbent to be “Not My President.” Since the confirmation of Bret Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court went against the wishes of the Democrats in the Senate—largely because they had previously invoked the “nuclear option” of making judicial confirmation a simple 51-vote majority instead of the 60 votes formerly needed to override a potential filibuster—the party has called the legitimacy of the court itself into question.

People on the left now want the country run as a pure democracy rather than the republic of elected officials that the Constitution established. Without the Electoral College, which was put in place to give small states with scant population some parity with large states, the citizens of Los Angeles county would be able to outvote the citizens of the Upper Northwest from Minnesota to Idaho. Presidential elections are always strategic games of chess, trying to take and hold at least 270 electoral votes. The makeup of the Senate, with two Senators for every state regardless of size, protects the interests of small states that are out of sight and of mind of large state and big city politicians. The Electoral College is part of the “checks and balances” put into the Constitution to protect minority interests from the whims and tyrannies of the majority.

What I fear in this new direction is what the left now seems openly to want: revolution. A country’s government is just laws and procedures, words written on pieces of paper or, worse, loosely preserved in bits and bytes somewhere in computer memory. What makes those words work is the belief of citizens and their elected politicians in the principles behind them. We agree to these things being true and necessary. We dismiss them at our peril.

The Constitution has set up a mechanism to change any part of it or add to its effective structure through the amendment process. But that process is hard, requiring any amendment to get a two-thirds vote in the House and the Senate, or being ratified by two-thirds of the state legislatures meeting in a special convention. The idea is that any change has to be popular enough and gain enough bipartisan support to pass this hurdle. We’ve done it twenty-seven times over the years, addressing issues as important as the voting rights of former slaves, women, and people age eighteen to twenty-one, and issues as ephemeral as the drinking habits of the average citizen.

The radical notion of changing or abolishing elements of the government or the Constitution itself by popular vote would invite a landslide. We have seen something of that kind operating in California, where initiatives are placed on the ballot by petition and voted on by the public at large. Those that pass acquire the force of law. Some initiatives have had good effects, some bad. But all are subject to the same verbal tricks and legal manipulations of any advertising campaign: claiming to support one thing while actually undermining or subverting it. Popular politics is a rough game to play.

The edifice of the U.S. government is fairly robust and can stand to have a few bricks knocked loose from time to time. But a popular onslaught in the name of “revolution”—whether meant picturesquely or in deadly earnest—could lead to a collapse. We’ve seen that happen before: France in 1879, Russia in 1917, Cambodia in 1975. The problem is that immediate and necessary changes in government always start with well-meaning people who have goals, a plan, and a vision for the future. But once the structure collapses, anything goes. The process starts with essentially kind-spirited liberals like Jean-Paul Marat or Alexander Kerensky; it ends with closed-minded tyrants willing to spill vast quantities of blood like Maximilien Robespierre and Joseph Stalin.

My fear is that the people so innocently dreaming of and calling for revolution today are the nation’s Murats and Kerenskys. If they get what they want, these people will go up against a wall within about six months. Waiting in the wings are the Stalins and the Pol Pots. And they will not be so liberal or kind-hearted.