|

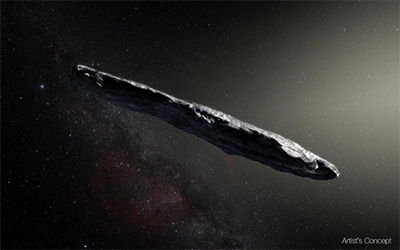

I have been thinking and blogging about the potential for finding and understanding aliens a lot recently, ever since reading Avi Loeb’s book on the interstellar object ‘Oumuamua, Extraterrestrial: The First Sign of Intelligent Life Beyond Earth. Now I am heading into realms that are totally unknowable—except from the viewpoint of what we know on Earth. But bear with me …

First off, I am not too interested—well, very, but not for the purpose of this meditation—in simply finding signs of life. We’ve seen things that could be confused with fossilized cells in the surface geology of Mars, and we suspect we might have found gases that could only be created by life-as-we-know-it in the atmosphere of Venus. When we get to other planets, both in this solar system and around other stars, we may well find chemical reactions and physical structures that we, from inside the realms of earthly biology and human understanding, define as “life.” Some of it may be intelligent but a lot of it, like most of the living forms on Earth, will not be what we choose to call “intelligent” or even “sentient.” Slime molds, for instance—honking huge single cells with eukaryotic nuclei—can move toward food and away from irritants in a fashion that seems to be intelligent or at least resembles neural networking.1 But it’s not going to build a rocket and come visit us.

When I think about aliens, I imagine the kind that will leave their planet and come out among the stars, as so much of Western-civilized humanity apparently hopes to do one day. And until we go out there, we’ll just have to wait for them to come to us.

So, first question. Will they look like us? Or even come close—like the various humanoid species that populate a Star Trek episode? I don’t believe it. As Carl Sagan once said, we’d have more success mating with a petunia than with an extraterrestrial lifeform.2

Earth has a long history of large, active lifeforms that might have developed intelligence but as far as we know did not. The dinosaurs come to mind: the family Tyrannosauridae and their cousins were bipedal, oxygen breathing, hunters and perhaps also scavengers, and probably—maybe—at the top of their food chain. But we have no evidence that they exhibited any real intelligence greater than that of a lion or house cat, wolf or dog, or even a shark. And yet the dinosaurs’ distant progeny, the Corvidae family—crows and ravens—as well as many other species of birds have a kind of intelligence we cannot explain. Even octopi—what? a mollusk?—exhibit a high level of intelligence. So size, shape, and mammalian ancestry are not necessarily prerequisites for intelligence. Still, none of these animals from Earth and its history is going to build a radio or a rocket anytime soon.

But the examples from Earth also suggest that we cannot expect to find our own kind of intelligence out among the stars, even if it wears an unexpected shape or inhabits an environment—like the earthly ocean of octopi and whales, or perhaps the liquid water under Europa’s ice, or the methane seas of Titan—in which humans don’t particularly thrive. Life on Earth did not, after all, start out on the land, although that’s probably the best place to build a radio or launch a rocket above the atmosphere.

One particular axis we are likely to encounter in alien psychology is that between the individual and the group. So far, on Earth, the sort of intelligence that is likely to expand to encompass curiosity, technology, and eventually space travel is fixed in individual entities. We humans are separate and complete persons inside our own bodies. We are socialized into groups, certainly, in which we can function for enhanced performance. But we do not become lost, stricken, enfeebled, and die when separated from our group—or at least not right away. And we see this pattern not only in human tribes but also in monkey troops, wolf packs, whale pods, cattle herds, and other social groupings.

Each of us knows or tries to find our place in the group, establish a niche where our capabilities and levels of aggression or empathy best fit, and seek comfort and contentment—or at least a subdued level of rebelliousness—in that placement. We are social animals. And that is the basis of all culture and intergenerational achievement. The fabled lone wolf, the mad scientist, the antisocial genius who works alone and keeps his notes in a secret code—such beings are of interest to us as fiction but they are not the creators of lasting culture or enduring civilizations. They build no great cathedrals, establish no great cities, lead no great social or political movements—and they don’t send rockets to the Moon.

So, we think, the kinds of intelligence we will find out among the stars will be like us in that: socialized individuals, each with his, her, or its own personality, preferences, anxieties, and dreams.

But we have another example on Earth to draw on: the hive mind. Whether in the beehive, the anthill, or the termite colony, the individual entities—the minds inside the separate bodies—are not really individuals as we humans understand the term. They are physically adapted to their tasks and place in the hive structure, and their minds are shaped—one might say innately programmed—to perform those tasks and not question their role. Even the queen is not a ruler or leader but simply the pampered sexual progenitor, the mother of them all, that ensures the colony’s survival and renewal.

Something of this was captured in the movie Star Trek: First Contact, where we are introduced to the Borg Queen (pictured nearby with Alice Krige playing the part). But although the Borg are a collective of mechanized humanoid lifeforms whose brains are electronically networked, they are not really a hive and the queen is not their mother nor their first member. The queen speaks with a voice and persona that can call up the collective mind but can also examine it, see its options and possible choices in context, contrast their existence with what she knows of humanity, and evaluate the Borg from the outside. She is more like a leader or first speaker than the sexual progenitor of the collective.

When we look to more imaginative literature on the idea of the hive as a society, the offerings are few. To my thinking, Frank Herbert has done some of the best work on this. His novel Hellstrom’s Hive examined what it would take to change human beings into the sort of social insects that could function most efficiently in the politically denuded world. And his novel The Green Brain imagined a hive of Amazonian insects that functioned as a single conscious entity, in the same way that the cells in our human bodies work together to create the reality—or perhaps it’s just the illusion—of a single person with independent will and desire.

We might encounter some variation of this colony structure, this collective intelligence that is not separated by the strands of individual personhood, out in the universe.

The question in my mind is whether this kind of intelligence is creative or merely reactive. A colony of honeybees or ants can adapt to its environment, find flowers or other foodstuffs when the weather is right, make its nest or hive nearby, and deal effectively with changes in environment and temperature, or else swarm to find a new nesting site. But can they only think and react to present and immediate needs? Could they eventually engineer changes in that environment? Could they look beyond the immediate locale and imagine ways to make it different? Could they look out at the stars and dream of visiting them? Or are they bound to the world as they know it, in a way that human societies are not?

Every group of socialized individuals is built of both leaders supported by their pack of generally submissive followers and then the potential outsiders, the rebellious youth and the mad geniuses, who question the social order, its structure and purpose, and seek something new or just different. At least, that’s how the human tribe has functioned and flourished. That is how we broke the bonds of merely reacting to our hunter-gatherer environment, engineered a better life through agriculture, created written records to preserve intergenerational knowledge, adapted invention and technology to improve everyday life, and then looked outward to the stars.

In our experience, based on that group of socialized individuals, progress depends upon imperfections in communication, upon differences of opinion and individual dreams, upon disagreements and conflicts. These are the one thing that the anthill or the beehive cannot survive. The resolution of these disruptions is never pretty and neat, and it’s never complete and finalized.

But without disruption and disquiet, you have the structured cooperation, the orderly processing and virtual stagnation, of the colony animal. That, or the brainless neural-net reactivity of the slime mold. And neither of them, I warrant, will be coming here anytime soon.

1. See, for example, Mycologist Explains How a Slime Mold Can Solve Mazes, from Wired.com in 2019.

2. But maybe we are connected after all, as in the panspermia hypothesis. See, for example, my meditation on The God Molecule from May 28, 2017.