|

|

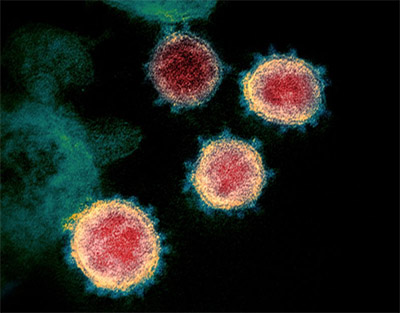

Image of the coronavirus taken with an electron microscope |

I generally try to keep these blogs (or essays, or meditations, whatever) away from absolute topicality and from following the news of the day in short order. My concern is the longer view, the background view, the why rather than the what of events. But the past few weeks have been extremely disturbing to all of us—emotionally, mentally, physically, and financially.

We have seen a virus of unknown quality as to its incubation time, severity of symptoms, transmission rate, and mortality arise and spread around the world in a matter of months—and perhaps, because of initial attempts at hiding the crisis, within just weeks. That has been one problem: governments, scientists, journalists, and anyone with social media access have lied, exaggerated, imagined, and spun counter-factual accounts (okay, “fake news”) about this virus and its effects. We have gotten comparisons—some real, some bogus, and some irrelevant—with the mortality associated with the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918, the H1N1 influenza pandemic of 2009, and the caseload and mortality of the yearly seasonal flu—as well as with deaths by gunshot and automobile. We hear that young people may get the disease and remain asymptomatic but still be carriers. We hear that older people and anyone with systemic vulnerabilities will likely get it and die.

In response to all this, various state governments around the world and in the U.S. have locked down their populations. In California, we live under a shelter-in-place order that has emptied the streets, reduced restaurants to take-out service only, closed all entertainments and public gatherings, and supposedly limits travel for non-essential workers to visiting the grocery store and pharmacy. Many other states have followed suit in this country. This has disrupted the local economy for goods and services, crimped the national economy for travel and tourism, and forced every business and organization to reevaluate its most basic assumptions and activities. The result has been people trying to stock up like doomsday survivalists and emptying grocery store shelves—including toilet paper, which seems to be the first priority for everybody.

As a personal experience, my local Trader Joe’s, where I went to do my weekly shopping on Monday, has instituted entry controls, attempting to limit store occupation to one hundred customers at a time. A clerk at the entrance monitors the queue outside and only lets people enter when a clerk at the exit signals someone has left the store. The queue path along the sidewalk is marked off with chalk at six-foot increments for “social distancing,” and we all advance by two giant steps each time someone up front enters. Inside the store, people are orderly and even pleasant—but at a distance. The number of Trader Joe’s personnel now almost equals the number of customers, and the shelves are reasonably stocked. At the register, a sign limits purchases to just two of any one item to prevent hoarding—although the checker let me get by with my weekly supply of six apples, six yogurts, and four liters of flavored mineral water. It wasn’t a bad experience, but it was sobering: we all seem to be taking these restrictions on our movements very calmly.

Health officials would like to see this personal lockdown extended for two, or eight, or perhaps eighteen months in order to “flatten the curve” of the virus’s exponential spread and keep the infected population from exploding as it apparently has done in China, Italy, and Iran. If these experts are right about the need for extending the restrictions, then local economies will crash. Small businesses, many large businesses, and whole industries like hotels, travel, and entertainment will go bankrupt or disappear. Unemployment will reach Depression-era levels, if not greater. China locked down its entire economy—or so it’s said—and dropped their gross domestic product by thirty percent—or so it’s said.

Because of uncertainty about all of this—fears of massive infection rates and millions of dead, the looming prospect of a cratered economy and worldwide depression—the stock market lost a third of its value in two weeks, ending the longest bull market in a sudden and dizzying bear market. The bond markets also crashed. The price of oil collapsed—although this had help from a price feud between the Saudis and the Russians. Gold prices spiked and then relapsed. There has been no safe place to invest in all of this turmoil.

The point of my bringing up these events in such detail is that we may have reached the limits of human accountability in a world still driven by natural forces. Whether the novel coronavirus—that is, this unknown version of a known type of virus—is the unfortunate meeting of a bat and a pangolin in a Chinese wet market, or the intentional creation of a weapon in a biosafety Level 4 lab, it still spreads by the vulnerabilities of the human immune system, the vagaries of human touch, and the viability of its own protein coat. Airline travel—which is virtually instantaneous these days, compared to horseback and sailing ship—allows the virus to move farther and faster before it touches down in a population and blooms with disease, and there it spreads in ways that are still hard to stop.

Today we all live with awareness of our scientific, medical, and technical capabilities, and so with a consciousness moral and civilizational superiority, compared to earlier times and less-developed places. Our past success with vaccines in treating viral diseases like polio and measles makes us believe that we should be able to quickly and easily prevent and treat this disease. We become impatient with diagnostic and pharmaceutical companies who can’t produce a rapid test or a vaccine within a matter of weeks.

We are capable of wielding such enormous economic power and organizational resources that we tend to believe we are immune to natural disaster. And so when hurricanes and earthquakes strike, or a virus comes into the population, we blame the response of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the Red Cross, the National Guard, and federal, state, and local governments as being inadequate to the task. Someone must be at fault for this.

We look at previous civilizations and historic events like the Spanish Flu, the Black Death, the eruption of Vesuvius, or the storms that swept the Armada’s galleons off course, and believe we are superior. Because we understand the nature of viruses and bacteria and their role in disease, or the nature of plate tectonics and its role in earthquakes and volcanoes, or the weather patterns that create typhoons and hurricanes, we think we should be able to prevent, treat, and immediately recover from their effects. And if we do not, we blame the experts, the government, the organizational structures that have been built to protect us. Someone should be held accountable.

The fact is, we are still relatively helpless. Humans are not the masters of this world, only its dominant tenants. We are still subject to the unpredictable movements of its lithosphere, its atmosphere, and the other inhabitants of its diverse biome, including the tiniest specks of DNA and RNA wrapped in a layer of reactive proteins.

No one gets the blame. Everyone is doing their best. And we all die eventually.