|

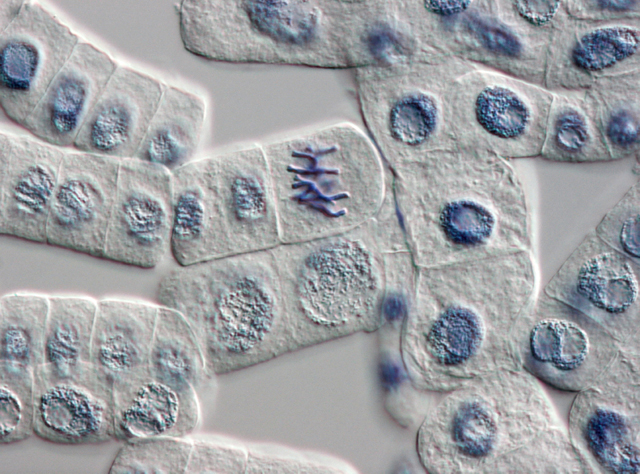

Consider that every human being alive today, and every creature that we would call alive, is part of an immortal cell line that goes back to the first life—probably some form of bacteria or blue-green algae—on this planet.1

You have come down through the ages, first as some kind of cellular life, then as a worm or starfish, then something with a backbone that lived in the sea, a chordate, a fish, then a fish with four stumpy limbs that crawled to the edge of the land, then an amphibian, a reptile, a mammal, a primate, and finally a human being. You have not necessarily been a prime example in the fossil record of any one of these creatures, because they were all fixed in form when they lived and died. But your cell line shares a common ancestor with each organism that can be found in the fossil record. You have ultra-great grandparents who are the parent to them all. We don’t have the same branchings, necessarily, but all humans have the same common ancestor somewhere, up the line, with sharks, spiders, sequoia trees, and slime molds.

We are the survivors. We are immortal. We are life itself.

We are in the direct cell line of the killers, too, who moved fastest to eat first rather than be eaten. We are the breeders, also, who chose quickly, pursued, and mated with the best example of our kind. We are the adapters, who were gifted by random mutation with the tool set to make the most of an ever-changing environment and survive on a malleable planet under a variable star.

In every parent going back to the one-celled predators—for we come most recently from the eaters, the animal line, rather than the chlorophyl-bearing, sun-absorbing plant line—we were the ones throughout history that stubbornly persisted, divided, grew up, bred, and survived to care for our young. The weak, the faint hearts, the maladapted died out and left no trace in the genetic record, although they may have solidified in the mud to join other examples in the fossil record. We are the winners of the race, the victors on this planet.

If we seem to be supremely well-adapted to the conditions on Earth, it is because our DNA has mutated—randomly, unexpectedly, sometimes with disastrously bad effect, sometimes with fortunately good effect, but mostly with no immediate effect until somewhere down the line that particular protein modification is needed—to stay in touch with and survive in the place where we happen to be. But we have also shaped the Earth itself, terraformed it to the needs of our particular kind of life.

The original atmosphere on Earth was formed in the outgassing of volcanos that accompanied the planet’s creation. They vented carbon dioxide, methane, ammonia, sulfur oxides, and water vapor. As air, none of this was breathable by any form of life that exists today. But those earliest blue-green algae converted sunlight and carbon dioxide into carbohydrates, the first building blocks and nutrients for other forms of life, and gave oxygen as their byproduct. This started the cycle that converted our atmosphere to the nitrogen-oxygen mix we all inhale today.

Similarly, life itself converted sterile rock, which water erosion and wave action had converted to sand grains and clay deposits, into the rich, dark, loamy soil that land-based plants need to survive. Generation after generation of living things dying in a particular place, being devoured by scavengers, worms, and bacteria, and then their traces being burned by the sun and distributed by the rain, contributed to making the planet’s surface more and more congenial to the life that would come after it.

Look around, and you can see the marks of life everywhere: the color of the sky, the shapes of the hills, the shoots of green plants poking up through the sandiest, least forgiving patches of ground, and the insects that come out of that ground every year. And we haven’t even gotten to the human presence yet.

Any straight line or smoothed curve you see, from the corners or roof lines of a building, the lanes in a road and its banked edges, the telephone and power lines strung across the landscape in a calculated catenary hanging between poles and towers, the planting of orchards and vineyards and the staking of fences and trellises—every instance of these things you see was conceived, planned, and placed by the hand of some human being. Every bridge that crosses a river or a bay on foundations of stone and wood or concrete and steel represents the choice of some human group that wanted to move themselves and their goods over there. Every village, town, or city that grew up beside river crossing, or the place where two trails met, or in a bay where you could pull up your boats, has its existence because some human group decided that here was a good place to live.

We have been on this planet a long time. If you look closely enough and read carefully enough, you can see how we have shaped it.

The question then—for both the world builders in fiction and the world explorers when we humans go out among the stars—is what marks we may find on the new planet telling of the life that has made its home there. No place is barren. Every place is a work of art in progress.

The next time you feel down, question the value of your life, and wonder what comes next, remember this. You are from the lineage of the stubborn, the survivors, the persisters, the winners. And you are still a work in progress. Nothing is barren. Everything lives, even when it dies.

1. Life has certainly evolved over time to adapt to the changing conditions on this planet, and it probably started out here as a bacteria or some other single-celled form. But whether the mechanism of that adaptation itself, the DNA-RNA-protein coding system, actually evolved on Earth from basic inorganic chemistry is still, in my mind, an open question. See, for example, Could DNA Evolve? from July 16, 2017.