|

|

Time, it seems, goes in only one direction. Or that is our current understanding of the laws of physics. Of all the dimensions of this place we call the universe, the only one that is unidirectional is time. Of course, we may not understand everything yet. And perhaps our sense of “time’s arrow” is based on our perceptions of cause and effect: if one thing follows another, they appear to be ordered in time. But time is malleable, stretching and collapsing according to the theory of general relativity, although still just going in the one direction we call forward, toward the future.

I am not here for a meditation on physics, however. The human brain is capable of working time both forward and backward. We encode short- and long-term memories that capture images, words, feelings, sounds, smells, and other artifacts of experience. Some people’s brains record everything they experience, every day, every minute, going back to first awareness. For most of us, the capture is more selective, usually affixed to experiences that left us with a strong emotional response. But some memories just get stored, almost randomly, and repeat themselves at the oddest of times or in scrambled contexts.1

We also use the mechanisms of the prefrontal cortex for planning and decision making, which are both projections of today’s activities into the future. We not only try to predict the future with our plans and decision, but we mentally inhabit a fictitious future with our hopes and daydreams—a false future that exists in our emotional lives as an alternative to the choices and possibilities that exist in the front part of our brain.

Human beings—and to some lesser extent other mammals—are the animals that can move forward and backward in time, using our brains. Our bodies, however, only travel the forward route, seeing planning and decision points pass by us like signposts along a highway.

A balanced human in an integrated life uses both functions. We look forward in expectation for the protection of ourselves and our families. We look backward in remembrance to give meaning to that expectation.

Some people live too much in the past. Those who have bleak or unknowable futures, or the very old with almost no future at all, tend to dwell on the past and their memories of a former life and loved ones as a means of sustaining their individuality. Some who have trauma or misdeeds in the past tend to dwell on them in a fretful attempt to change what has already occurred and, in their dreams, create a new current reality.

Some people live too much in the future. The very young look forward because everything that has gone before—especially if their life has been the mundane daily round of play and school, and interactions with parents and friends—is merely preparation for the life to come, creating a set of skills and responses that will carry the person into adulthood and beyond. Others more adult live for the future because their lives so far have been wasted—especially if drugs and alcohol, bad relationships, or bad choices and actions have been involved—and they can only look to the future to make amends, make a better life, or create new meaning for that life.

My own life, I realize now, toward the end of it, has always been frontally focused. I have always been considering, planning, and dreaming about the next day’s work, the next job, the next book to read or write, the next experience. I do recall the past and have pleasant memories of most of it, but I do not live there. I live in tomorrow, next month, next year. My head is always somewhere six months out.

When I was at the university and was already focused on studying English literature and a future as a writer—novels were always my first choice, although not the most lucrative part of my eventual writing career—I took a course on Predicting the Future. This was part of that academically silly season in the late 1960s, when campus radicals were demanding courses with more “relevance”—by which they meant to steer away from the traditions of Western Civilization. But my mentor, the science fiction author who wrote under the pen name William Tenn, took advantage of the opportunity to inject a bit of his favorite subject into the teaching. We read the current crop of futurist authors and a bit of predictive science fiction, and we studied the ways people have tried to know what’s coming next. For example, I wrote term paper on Tarot cards as a method of fortunetelling.2

But now, in my seventy-third year, I find that looking forward has disturbing possibilities. There aren’t that many new experiences, possibilities, or choices out there ahead of me. Sometimes the future seems like a narrow, gray space, like the last few pages under your thumb in a book that you are reading and enjoying, whose plot you are following, and whose climactic moment has not yet come, and you’re not sure there are pages enough, time enough, to make a suitable ending. Six months out used to be a long time for me. Now, on some days, it seems to be all the time that is left—even though I am still healthy, strong, eating right, exercising, healing well, and hopeful. But just … how much more can I expect from life?

It’s not a terrifying thought … yet. But when you can sense the Great Darkness somewhere beyond that gray space, it makes you pause and consider your past life choices.

1. And, as research into “false” or altered memories has suggested, every time we recall a memory, our brain does a little editing—maybe a bit of improvement, sometimes a bit of damage—that changes the memory for future recall. Nothing is fixed in our brains, like an engraving on a steel plate. Instead, everything is more malleable, like the silver nitrate in a film emulsion, which can be affected by later exposure to light, or the digital bits in a computer memory, which get translated out of storage and then translated back into storage, with changes and degradations going both ways. Our brains are more a fluid “chemical pot” than a hard-wired “electric box.”

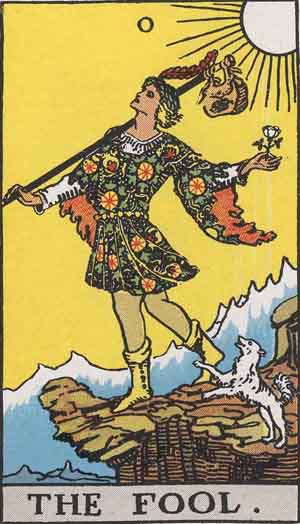

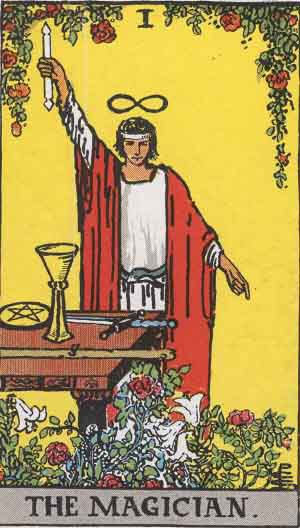

2. Actually, the Tarot—particularly in the 22 cards of the Major Arcana—is a story of human struggle and conflicting values that stands in opposition to the Judeo-Christian tradition. It relates the life transition of every aware soul from the insouciant and careless Fool of Card 0 to the powerful and careful Magician of Card 1. It’s a story of personal development.