|

For those of us enamored of the Dune ethos,1 I have a new commandment to add to the Butlerian Jihad: “Thou shalt not deny the agency of a human being.” This goes along with the broader and more restrictive, “Thou shalt not create a machine in the likeness of a human mind.” My addition, though apocryphal, completes the thought.

What do I mean by agency? First, it is the ability of a human being to act in all parts of life and includes by implication free will. Humans are free and unrestrained in what they may think, say, and do. This does not mean unbridled. The process of education and socialization that every human child undergoes includes lessons in what is right, proper, and true in thinking—which may vary from culture to culture. It includes lessons, sometimes painful lessons, in what is proper or discreet to say, and in what is right and proper to do. And again, these may vary from culture to culture and from setting to setting.

This commandment also does not imply that other humans may not take exception to the expressed thoughts, spoken words, and actions of other human beings. If one person’s free will and agency leads him to insult another, to break the posted speed limit, or to commit murder, there may be—sometimes must be—consequences. And the intelligent mind will weigh the probability of their occurrence and their outcome in the thinking that goes into speaking and acting.

Things that infringe upon and are an affront to human agency are enslavement and the narrow strictures that may be imposed by church, party, society, and state.

We resent enslavement because our will and our scope of action are denied to us: we can be punished, even killed, if we refuse to follow the orders of others in every aspect of life, even to valuing and caring for our families. Some humans may accept the orders and conventions imposed by the slave master as if they were laws to be obeyed. Sometimes they are laws, written into the statutes of the society that keeps slaves and protects slave owners. But those would then be laws against human liberty and agency, and so in violation of this commandment.

We may chafe under the strictures of a confining religious precept, the bounds of party loyalty, the adherence to social norms, or the laws and regulations of an administrative state that bind us with both demands to speak and perform in certain ways and injunctions on speech and action that we might want to take. With these restrictions of religion, party, society, and government, the threat against free agency is the consequence of being shunned by our co-religionists, removed from the party rolls, outcast from our family and friends, or losing our citizenship and in some cases receiving probation and jail time. We may understand the reasons and the reckoning in these cases, but the limits on our actions still chafe. Ultimately the individual must decide, as above, if the benefits of membership or citizenship are worth complying with the strictures. These conditions would not, however, be a violation of the commandment unless the penalty in all cases was imprisonment or death.

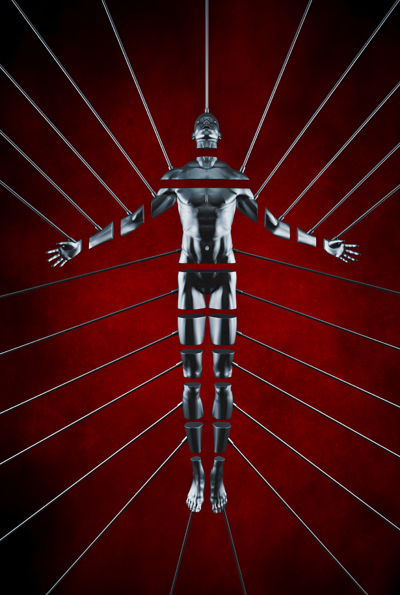

And yet … the religion, political party, social convention, or government statute that imposes too strict a set of conditions for membership must be aware of and weigh the risks it runs: internal revolt, structural revision, or mass renunciation by those who will not put up with the burdens of compliance. Every leader in every situation involving large numbers of human beings must calculate the risks and rewards of trying to impose too precise, complex, or complete a set of requirements on the people he or she intends to lead. Human beings are not puppets. They have eyes, ears, and minds, and those minds make decisions based both on the rules and promises they are given and on the consequences they can determine on their own. That is the fulcrum upon which human agency balances.

Recognition of and respect for individual human agency is the foundation of the principles of free thought, free speech, and free action. Without the one, you cannot have the others.

1. See my blog The Dune Ethos, from October 30, 2011.