|

Consider that the universe right after the Big Bang1 was a small, cold, rapidly expanding cloud of mostly hydrogen nuclei—that is, protons—and loose energy like gamma rays, x-rays, and microwaves. Just a mist of mostly non-reactive stuff: protons eventually gathering electrons to themselves and clinging to each other, holding hands and heading away into the darkness.

That is a universe in which life could not exist. Two molecules of diatomic hydrogen rubbing together would create no more than transitory friction. And then they would bounce away. It wasn’t until the outward flight slowed down a bit and gravity could take over that things started to happen.

When things began cooling down and those hydrogen atoms could approach each other, gravity drew them together. And when enough hydrogen atoms got close enough, jostling against each other, the inward pressure ignited a fusion reaction. Then hydrogen atoms became helium atoms, and the energy that was released heated the mix, so that outward pressure from excited gases balanced the attraction gravity. And then there was light and heat in the universe.

The fusion reactions created successive combinations of protons and eventually included neutrons. When the hydrogen at the center of a star begins to run low, helium nuclei fuse to become carbon. Then carbon fuses to oxygen and neon, and oxygen fuses to become silicon and sulfur. The process continues until iron atoms begin to form. These nuclei are too heavy for normal stars to fuse, the fire starts to die down, and the star eventually first collapses and then explodes. Pressures inside that explosion fuse the heavier atoms and scatter everything to great distances—out to where dust and gas can begin forming new stars with richer content.

Generations of repeated fusion and collapse provided the atoms and molecules that are the basic building blocks of life. Dust and gas also formed the planets around those later stars, providing the environments in which life could form. And the stars themselves provided the energy in the form of heat and light for various atoms with their complex electron bonding to join into molecules that could react with each other.

This process takes place in not just our solar system or our own Milky Way galaxy, but inside the 100 billion to two trillion galaxies that spread across the visible universe. Everywhere we look, we can see points of light representing stars. And we know of almost 6,000 extraterrestrial planets in our local neighborhood alone. Many of them are close enough to their star to have liquid water—the molecule comprising hydrogen and oxygen—in their makeup without being so close that their surfaces are scorched earth nor so large that they are simply balls of dense gas without an underlying surface. Water and someplace to put it are the basis of life—at least the kind of life we know and understand.

So, the building blocks, the environment, and the driving energy of life is all around us, out as far as the eye can see. And that means life itself must be all around us.

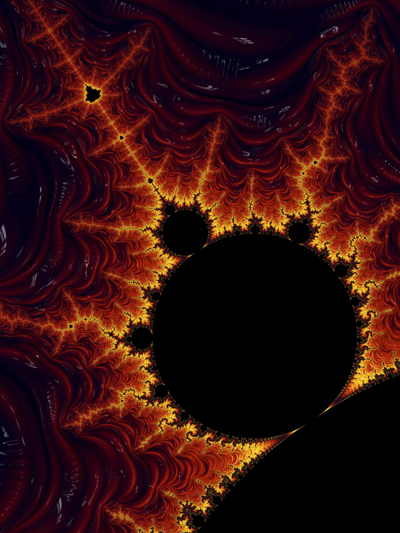

1. Well, if you can accept the Big Bang, a microparticle containing all the matter in the now-visible universe, compressed to an intense point, denser than a black hole’s heart, as the starting point of all that we now can detect. We only believe in this incredible situation because we noticed the universe was expanding in all directions. Then we calculated a rollback and decided it started somewhere as a point of nothing about 13 billion years ago. And everything since then has been theory and mathematics. In my opinion, the Big Bang is another creation myth, like God dividing the firmament, and no one really knows.

No comments:

Post a Comment